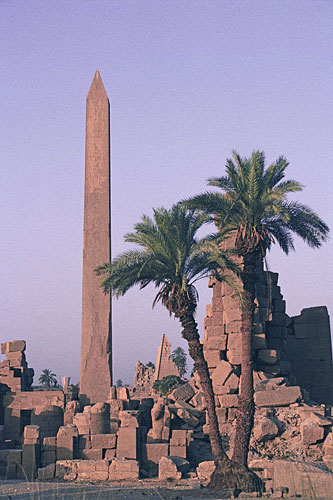

Obelisk of Queen Hapshetsut, Karnak, Egypt

In Upper Egypt, on the eastern bank of the Nile, stand the remains of the most extensive temple complex of the Dynastic Egyptians. The entire site was called Wast by the Egyptians, Thebai by the Greeks, and Thebes by the Europeans (the word Thebai derives from the Egyptian word Apet, which was the name of the most important festival held each year at Luxor). A large proportion of the ruins of ancient Egypt are situated here, divided between the temples of Luxor (from the Arabic L'Ouqsor, meaning 'the palaces') and the temples of Karnak (this name deriving from the Arab village of Al-karnak). The ruins of both these temple complexes cover a considerable area and are still very impressive. Nothing remains, however, of the houses, markets, palaces and gardens that must have surrounded the temples in ancient times. The principal feature in Egyptian social centers, and usually the only one to have survived, was the temple. Not a place for collective worship but rather a house of the gods, only the temple's priests and the high nobility were allowed to enter the inner sanctums. The temple did, however, act as a cohesive focal point for the local community, which participated in the numerous pilgrimage festivals and processions to the temple.

Recent excavations have pushed the history of Karnak back to around 3200 BC, when there was a small settlement on the bank of the Nile where Karnak now stands. The great temple complex at Karnak is, however, mostly a Middle Kingdom creation. Archaeological excavation reveals that the complex was in a near constant state of construction and deconstruction, and that almost every king of the Middle Kingdom left some mark of his presence at Karnak. The central temple at Karnak was dedicated to the state god, Amon, and is directionally oriented to admit the light of the setting sun at the time of summer solstice. Just north of this temple are the foundations of an earlier, but also central and primary, temple dedicated to the god Montu. Little remains of this temple, not because it was weathered by the elements, but rather because it was systematically deconstructed and its building stones later used in the construction of other temples. According to Schwaller de Lubicz, this mysterious dismantling of temples, found at Karnak and numerous other places in Egypt, has to do with the changing of the astrological cycles. The supplanting of the bull of Montu with the ram of Amon coincides with the astronomical shift from the age of Taurus, the bull, to the age of Aries, the ram; the earlier temple of Montu had lost its significance with the astronomical change and thus a new temple was constructed to be used in alignment with the current configuration of the stars.

The photograph shows an obelisk erected by Queen Hatshepsut (1473 -1458 BC). It is 97 feet tall and weighs approximately 320 tons (some sources say 700 tons). An inscription at its base indicates that the work of cutting the monolith out of the quarry required seven months of labor. Nearby stands a smaller obelisk erected by Tuthmosis I (1504 - 1492 BC). It is 75 feet high, has sides 6 feet wide at its base, and weighs between 143 and 160 tons. Hatshepsut raised four obelisks at Karnak, only one of which still stands. The Egyptian obelisks were always carved from single pieces of stone, usually pink granite from the distant quarries at Aswan, but exactly how they were transported hundreds of miles and then erected without block and tackle remains a mystery. Of the hundreds of obelisks that once stood in Egypt, only nine now stand; ten more lay broken, victims of conquerors, or of the religious fanaticism of competing cults. The rest are buried or have been carried away to foreign lands where they stand in the central parks and museum concourses of New York, Paris, Rome, Istanbul and other cities.

The use of the obelisks is even more of a mystery than their carving and means of erection. While the obelisks are usually covered with inscriptions, these offer no clue to their function, but are instead commemorative notations indicating when and by whom the obelisk was carved. It has been suggested that the erection of the obelisk was a gesture symbolizing the 'djed' pillar, the Osirian symbol standing for the backbone of the physical world and the channel through which the divine spirit might rise to rejoin its source. John Anthony West notes that the obelisks were usually erected in pairs, one obelisk being taller than the other, and that the dimensions of the obelisk and the precise angles of its shaft and pyramidion cap (originally plated in electrum, an alloy of silver and gold) were calculated according to geodetic data pertaining to the exact latitude and longitude where the obelisk was set. "The shadows cast by the pair of unequal obelisks would enable the astronomer/priests to obtain precise calendrical and astronomical data relevant to the given site and its relationship to other key sites also furnished with obelisks." Readers interested in the fascinating subject of obelisks should consult The Magic of Obelisks by Peter Tompkins and The Orion Mystery by Bauval and Gilbert.

Ankh Carving, Karnak, Egypt

Obelisks in Ancient Egypt; Archaeology Magazine

Ancient Egyptians adorned their temple facades with pairs of obelisks to honor their gods and recall the great deeds of their pharaohs. With four rectangular sides covered with hieroglyphic inscriptions, the obelisk is designed to lead the viewer's eye toward the sky, tall and straight ending in a four-sided pyramid. The obelisk originated during Egypt's Old Kingdom (2584-2117 B.C.) as a small solid structure associated with the sun-deity Re. Pharaoh Senworset I (1974-1929 B.C.) constructed the first giant obelisk at Heliopolis during the Middle Kingdom (2066-1650 B.C). Giant Egyptian obelisks weigh hundreds of tons and are composed of solid pieces of granite quarried at Aswan in southern Egypt. Modern obelisks, big and small, are found all over the world and the U.S. from the Washington Monument, to war memorials, to the grave markers of presidents (Washington, Jefferson, and Lincoln's tombs all include obelisk memorials). New York City is filled with obelisks, and a tour of them will take you all over Manhattan and beyond to view monuments, tombstones, and even an authentic Egyptian original, known as Cleopatra's Needle. But how and why did the obelisk become and remains so popular?

Foreign fascination with Egypt is as old as Egypt itself. Even before Alexander the Great conquered Egypt in 332 B.C. Greek travelers took trips up and down the Nile, leaving graffiti on monuments and transporting exotic materials home. Under the Ptolemys, Greek kings who ruled Egypt from 332-30 B.C., Greeks living in Egypt adapted some aspects of Egyptian culture, from deities to mummification. But it was the Romans who first loved obelisks. After the Romans conquered Egypt in 30 B.C., they carted off a vast number of obelisks and today, more Egyptian obelisks stand in Rome, 13 total, than in all of Egypt. After the fall of Rome, no Egyptian obelisk would leave the shores of the Nile again until the 19th century. During the Middle Ages, knowledge of Egypt was limited mainly to Biblical contexts: Egypt was the land of Moses, Saint Mark and Anthony; it had sheltered the Holy Family. The few Europeans who ventured to Egypt went on pilgrimage or were drawn there by the crusades or commerce. With the Renaissance and its classical revival Egyptian motifs became more familiar. Egyptian themes appeared in art and architecture and Pope Sixtus V (1585-1590) moved and re-erected an obelisk (originally brought from Heliopolis, Egypt to Rome by the emperor Caligula) from its ancient site in the Circus of Nero to its current location, about 260 yards away, in Saint Peter's Square in the Vatican. In the mid 17th century Gian Lorenzo Bernini kept the obelisk as the centerpiece in his own redesign of St. Peter's.

In the 18th century during the Enlightenment, the obelisk began to symbolize eternity and memorialization, and it became a popular form of commemoration for victories and heroes by the Europeans. Egypt was visited by occasional outsiders during the 17th and 18th centuries who often carted home small objects like amulets, but Egyptian Revival style (including obelisks) and Egyptomania gained wide popularity thanks to Napoleon's campaign in Egypt (1798-1799) and with the publishing of Vivant Denon's Voyage dans la Basse et la Hautes Egypt (1802) and Description de l'Egypte (1809). With the invention of the steamship in the 1840s, traveling to Egypt became much faster and efficient for Europeans and Americans. Many more Westerners made the journey to Egypt's warm climate. Ever growing publications dedicated to the subject of Egypt further enticed travelers to make the trip, and at the very least inspire decoration in the Egyptian-style. In the early 1800s some Europeans, such as British consul-general Henry Salt, French consul-general Bernard Drovetti, and Italian strongman and proto-archaeologist Giovanni Battsita Belzoni collected artifacts to ship back to European institutions like the Louvre and the British Museum, which were beginning to establish their collections.

In the U.S., obelisks appeared in the late 18th century as memorials. Some early examples include the Columbus Memorial in Baltimore, which was built in 1792 to honor the 300th anniversary of Columbus' discovery of the New World, and the Battle of Lexington obelisk in Massachusetts, designed in the 1790s to commemorate those Americans who had perished in the first battle of the Revolutionary War. Obelisks continued to increase in popularity, and during the Civil War, they became even more common as grave markers and memorials. Today, the obelisk is a common sight in cemeteries across America, standing as memorials to the deceased.

In the early 19th century, obelisks became symbolic of international diplomacy and trade relations with Egypt: the Khedives of Egypt (dynastic rulers of Egypt who began their legacy with the Ottoman Sultan's appointment of Muhammad Ali in 1805) presented three as gifts. Two, erected by Thutmose III (1479-1424 B.C.) in Heliopolis, and moved to Alexandria by Augustus, were given to Britain and the United States. The third, placed by Ramesses II (1279-1212 B.C.) in Luxor, was awarded to France.

Britain was awarded one of the Alexandria obelisks, known as Cleopatra's Needles, In 1819 by Egypt's leader Muhammad Ali (1769-1849), a Turkish man who was appointed by the Ottoman Sultan to oversee Egypt and Sudan, and who steered Egypt toward modernization. The obelisk waited in Alexandria until it was eventually shipped over in 1877. The crossing was hard and tragic (some six sailors perished), but the obelisk survived the trip and now sits on the banks of the Thames in City of Westminster near the Golden Jubilee Bridges. The six deceased sailors' names are on a plaque on the base of the obelisk. Muhammad Ali presented France with its Luxor obelisk in 1826. It was moved to France in 1833 where King Louis Philippe re-erected it in the Place de la Concorde where the guillotine had sat. It was meant to serve as a monument to memorialize King Louis XV and those who lost their lives during the French Revolution. The third obelisk, the other Cleopatra's Needle, was awarded to the United States in 1879 and was moved in 1880.

Martin Gray is a cultural anthropologist, writer and photographer specializing in the study of pilgrimage traditions and sacred sites around the world. During a 40 year period he has visited more than 2000 pilgrimage places in 165 countries. The World Pilgrimage Guide at sacredsites.com is the most comprehensive source of information on this subject.

Martin Gray is a cultural anthropologist, writer and photographer specializing in the study of pilgrimage traditions and sacred sites around the world. During a 40 year period he has visited more than 2000 pilgrimage places in 165 countries. The World Pilgrimage Guide at sacredsites.com is the most comprehensive source of information on this subject.For additional information:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karnak